Democratic governance and policy complexity: revisiting the intelligence of democracy

Abstract

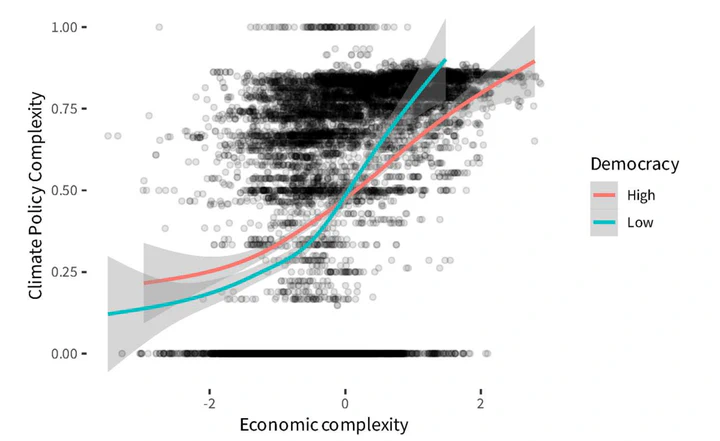

Democracies are praised for managing complex problems, yet ballooning rule stocks may erode their effectiveness and legitimacy. We ask whether this ‘complexity trap’ is uniquely democratic. Building on theories of participatory and deliberative governance, we hypothesise that countries with higher democratic quality generate a higher baseline of policy complexity but adapt more smoothly as problems grow, while less-democratic regimes initially regulate sparsely yet see complexity surge with mounting challenges. Using an original dataset covering the climate-policy portfolios of 134 countries from 1998–2022, we measure external problem complexity, policy complexity, and regime characteristics. Several models reveal that problem complexity drives policy complexity everywhere, but interaction effects confirm our expectations: more participatory and deliberative systems absorb additional complexity more gradually than their less democratic counterparts. The findings nuance fears of democratic self-overload, showing that institutional openness creates not only complexity but also resilience. Our results challenge deterministic decline narratives, confirm the relative intelligence of democracy, and inform debates on effective, legitimate climate governance worldwide.

Online appendix

The online appendix contains an extension of the procedures and results presented in the paper.